201 ways to say f***: How the world swears

Our brains swear for good reasons: to vent, cope, boost our grit and feel closer to those around us.

Swear words can act as social glue and play meaningful roles in how people communicate, connect and express themselves — both in person, and online.

More than 1.7 billion words of online language across 20 English-speaking regions have been analysed in new research published in Lingua, a peer-reviewed journal covering general linguistics.

Know the news with the 7NEWS app: Download today

This has been narrowed down to 597 different swear word forms — from standard words, to creative spellings like 4rseholes, to acronyms like wtf.

The findings challenge a familiar stereotype. Australians — often thought of as prolific swearers — are actually outdone by Americans and Brits, both in how often they swear, and in how many users swear online.

Facts and figures

The study focused on publicly available web data — such as news articles, organisational websites, government or institutional publications, and blogs, but excluding social media and private messaging.

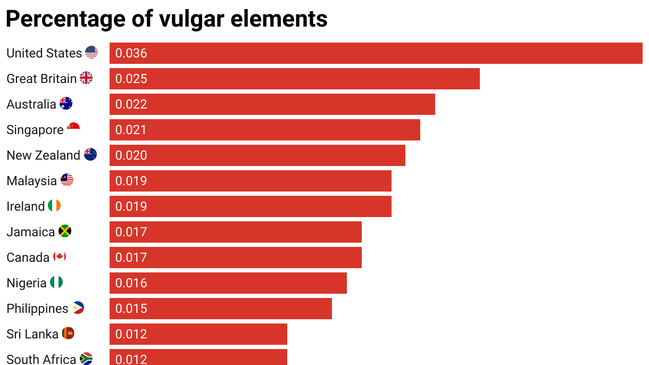

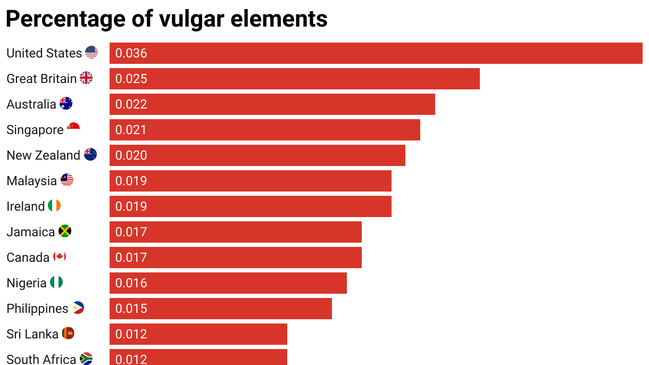

It found vulgar words made up 0.036 per cent of all words in the dataset from the United States, followed by 0.025 per cent in the British data and 0.022 per cent in the Australian data.

Although vulgar language is relatively rare in terms of overall word frequency, it was used by a significant number of individuals.

Between 12 per cent and 13.3 per cent of Americans, around 10 per cent of Brits, and 9.4 per cent of Australians used at least one vulgar word in their data.

Overall, the most frequent vulgar word was f*** — with all its variants, it amounted to a stunning 201 different forms.

The study focused on online language that didn’t include social media, because large-scale comparisons need robust, purpose-built datasets. It used the Global Web-Based English (GloWbE) corpus, which was specifically designed to compare how English is used across different regions online.

So how much were the findings influenced by the online data researchers used?

Telling results come from research happening at the same time. One study analysed the use of f*** in social networks on X — formerly known as Twitter — examining how network size and strength influence swearing in the UK, US and Australia.

It used data from 5,660 networks with more than 435,000 users and 7.8 billion words and had the same results.

Americans use f*** most frequently, while Australians use it the least, but with the most creative spelling variations — some comfort for anyone feeling let down by our online swearing stats.

Teasing apart cultural differences

Americans hold relatively conservative attitudes toward public morality, and their high swearing rates are surprising.

The cultural contradiction may reflect the country’s strong individualistic culture. Americans often value personal expression — especially in private or anonymous settings like the internet.

Meanwhile, public displays of swearing are often frowned upon in the US. This is partly due to the lingering influence of religious norms, which frame swearing — particularly religious-based profanity — as a violation of moral decency.

Significantly, the only religious-based swear word in the study’s dataset, damn, was used most frequently by Americans.

Research suggests swearing is more acceptable in Australian public discourse. Certainly, Australia’s public airing of swear words often takes visitors by surprise.

The long-running road safety slogan “If you drink, then drive, you’re a bloody idiot” is striking — such language is rare in official messaging elsewhere.

Australians may be comfortable swearing in person, but the study’s findings indicate they dial it back online — surprising for a nation so fond of its vernacular.

In terms of preferences for specific forms of vulgarity, Americans showed a strong preference for variations of asshole, the Irish favoured feck, the British preferred c***, and Pakistanis leaned toward butthole.

The only statistically significant aversion found was among Americans. They tend to avoid the word bloody, which folk wisdom claims is blasphemous.

Being fluent in swearing

People from countries where English is the dominant language — such as the US, Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Ireland — tend to swear more frequently and with more lexical variety than people in regions where English is less dominant like India, Pakistan, Hong Kong, Ghana or the Philippines.

This pattern holds for both frequency and creativity in swearing.

But Singapore ranked fourth in terms of frequency of swearing in the study, just behind Australia and ahead of New Zealand, Ireland and Canada.

English in Singapore is increasingly seen not as a second language, but as a native language, and as a tool for identity, belonging and creativity.

Young Singaporeans use social swearing to push back against authority, especially given the government’s strict rules on public language.

One possible reason the study saw less swearing among non-native English speakers is that it is rarely taught.

Despite its frequency and social utility, swearing — alongside humour and informal speech — is often left out of language education.

Cursing comes naturally

Cultural, social and technological shifts are reshaping linguistic norms, blurring the already blurry lines between informal and formal, private and public language.

Just consider the Ausstralian contributions to the July Oxford English Dictionary updates: expressions like “to strain the potatoes” (to urinate), “no wuckers” and “no wucking furries” (from “no f***ing worries”).

Swearing and vulgarity aren’t just crass or abusive. While they can be used harmfully, research consistently shows they serve important communicative functions — colourful language builds rapport, expresses humour and emotion, signals solidarity and eases tension.

It’s clear that swearing isn’t just a bad habit that can be easily kicked, like nail-biting or smoking indoors.

Besides, history shows that telling people not to swear is one of the best ways to keep swearing alive and well.