From New York to Manila, Butch Meily brings Reginald Lewis’ story to Filipinos

MANILA, Philippines – On a rainy Sunday afternoon, Filipinos gathered in Bonifacio Global City not just for a book launch, but a story that had made its way from New York to Manila.

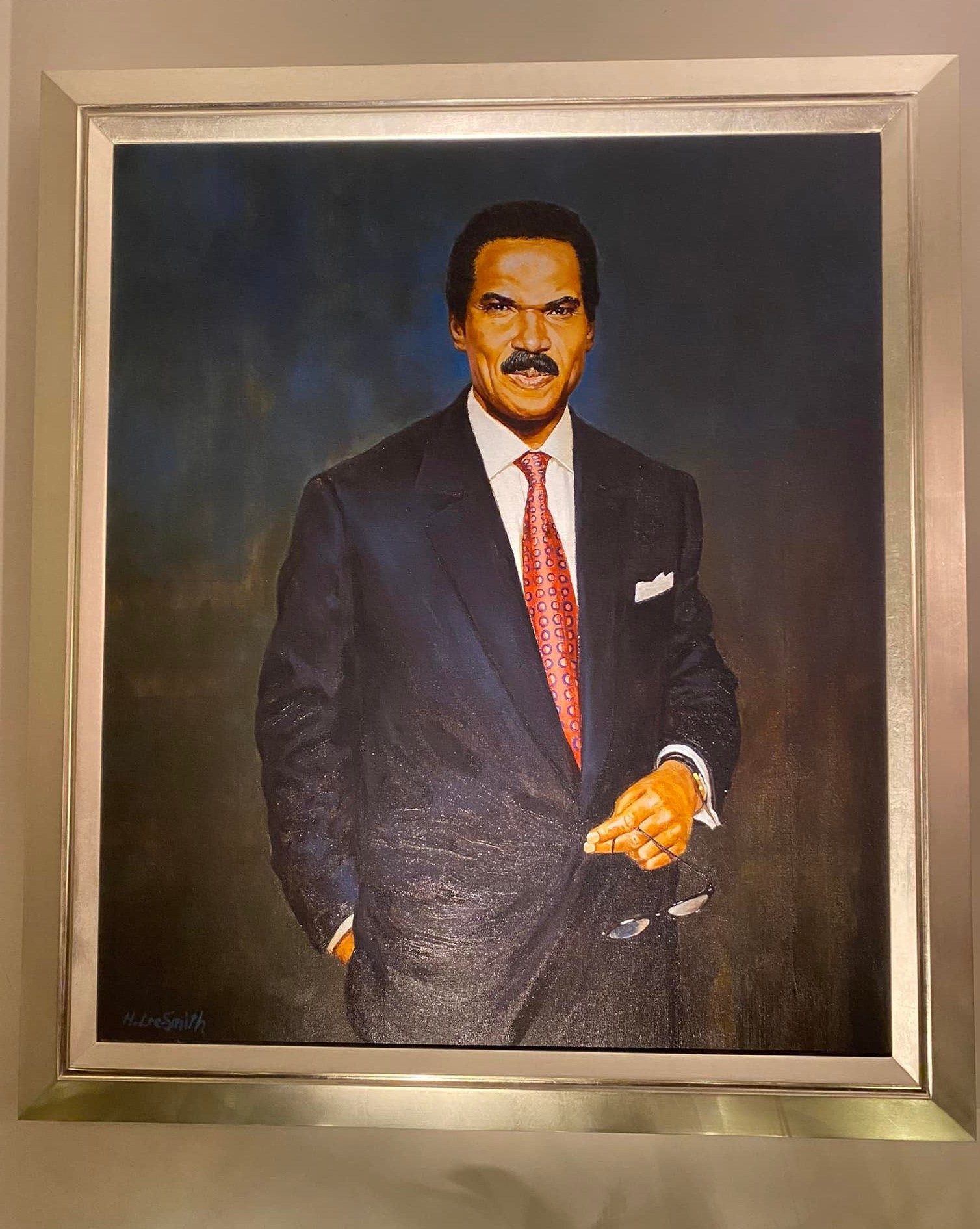

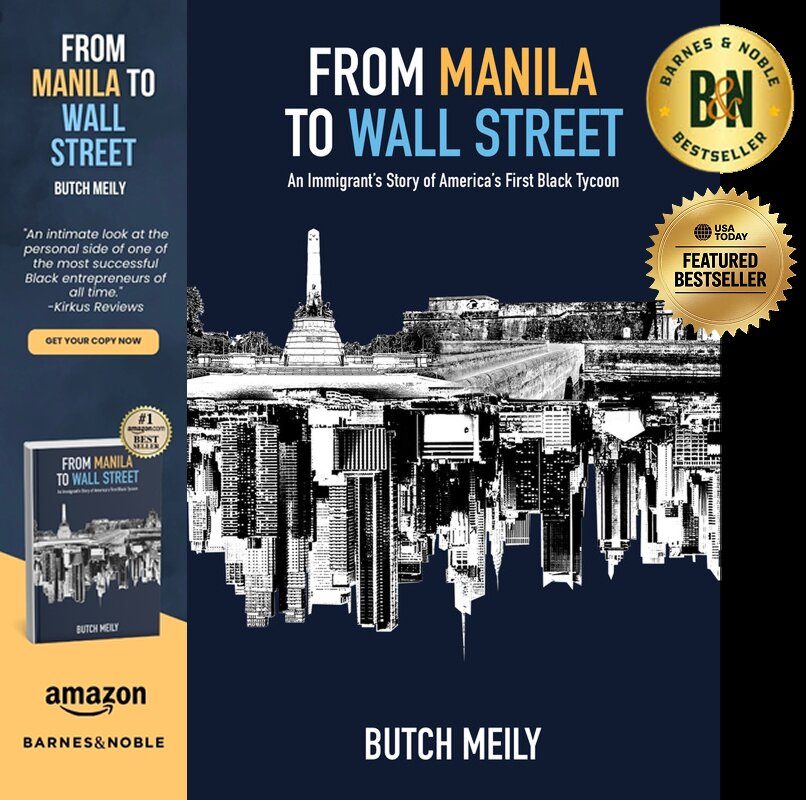

In From Manila to Wall Street: An Immigrant’s Journey with America’s First Black Tycoon, public relations executive, author, and social impact leader Butch Meily recounts his life alongside Reginald Lewis, the first African American to build and lead a billion-dollar global company, breaking racial barriers in Wall Street — who was also Meily’s partner in PR.

The event, held at Fully Booked BGC and attended by family, friends, and stage actors who performed excerpts from the book, marked a poignant homecoming.

“It took me 40 years to get here,” Meily said, recalling his long journey from a corporate office in New York to a deeply personal reflection on ambition, race, regret, and legacy.

‘Larger than life’

“Keep going, no matter what,” was Reginald Lewis’ motto, and it’s a saying Meily hopes will stay with young readers.

“No matter what happens, when somebody knocks you down, whether it’s race, whether it’s your personal confidence, whatever the problem is, whether you have a tough boss, you’ve got to pick yourself up and do it,” he said.

Lewis — who came from a semi-tough, poor neighborhood in Baltimore, and reached the pinnacle of corporate America — was “larger than life,” said Meily.

A Harvard Law graduate, Lewis lived without apologies. He fought for a Fifth Avenue residence where Black Americans were unwelcome. He owned a mansion in the Hamptons that mysteriously burned down. He never stopped pushing boundaries — not in real estate, not in business, not in life.

“He always wanted something else,” Meily recalled. “He wanted to be in a Paris apartment — he wanted the best. He wanted an apartment in the Rockefeller building, with the sister of Jackie Kennedy living next to him. He wanted a mansion in the Hamptons — he wanted the biggest mansion in the Hamptons. He wanted a personal play; he had an artist paint something original — an original artwork for the play. So it was always something more.”

“He was the first Black person to bid a billion dollars for a company,” Meily said. “He overcame so many barriers, especially his race, and all the discrimination. And yet he reached the top.”

But the story isn’t just Lewis’ — it’s also Meily’s. It’s the story of a Filipino immigrant carving out a place in 1980s corporate America, gradually reckoning with how race is experienced differently across Black and Asian communities, and realizing that while ambition can break barriers, it also leaves things broken behind.

“I wish I had done things differently,” Meily admitted during the Q&A. “Maybe I should have spent more time with my family. Maybe I should have spent more time with my ex-wife. Maybe I should have been nicer to her. You know, so I have plenty of regrets.”

And those regrets help form the emotional undercurrent of a story that isn’t just about success, but also about what’s sacrificed in pursuit of it. And for Meily — an immigrant chasing the American dream — those sacrifices looked very different from the ones Lewis had to make. Their partnership thrived across difference, but was also shaped by it.

Two men, two worlds

At the heart of From Manila to Wall Street is not just a story of two men, but of two worlds colliding. Meily, a Filipino immigrant, carried with him the optimism that the American dream still promised — that hard work and talent could overcome background, and that merit alone could earn opportunity. But Lewis carried a different inheritance — one shaped by systemic exclusion, racial trauma, and a lifetime of being told where he could and couldn’t belong.

“Neither of you understand. When you’re Black in this country, they lead you to the water, but they won’t let you drink,” Lewis once told Meily and his wife Loida, also a Filipina. “As a Black man, I don’t just want a seat at the table. I want to sit at the head of the table. You Filipinos have this candy cane vision of America that doesn’t exist,” Meily writes in his book.

“I think all Filipinos are racists basically, although I never sensed that with you, Butch,” Lewis continued, accusing Meily of viewing the US through the rose-tinted lenses of Hollywood movies.

“You don’t know. But every Black guy worth his salt grows up with a sense of anger. Every time I score, I kick the shit out of the lie that Blacks aren’t good enough. You can be as rich as anyone, but when a cop pulls you over, you’ve got to be extra careful,” said Lewis.

In the book, Meily reflects on this difference, and how the concept of race, for Black Americans, is something born into: systemic and inescapable in a way that many immigrants, including Filipinos, might not fully comprehend. Maybe, he suggests, this disconnect stems from the country’s long colonial history under Spain and the US, which left many Filipinos looking down on those with darker skin.

Despite his own experiences with racism, Meily notes that what he faced was often subtle: casual slurs, quiet prejudice at supermarket lines. For Lewis, it was a lifelong inheritance, visible from birth, and impossible to ignore.

And yet, Meily insists, Lewis’ story remains universal. That the story of resilience, of the outsider overcoming different barriers and reaching the top is one that resonates with people everywhere. “Especially Filipinos and especially Filipino-Americans,” he told Rappler. “Race is an issue that we have to grapple with. And it’s even more true now than it was in other times in the past. And I think people are scared now.”

“So I think it’s the type of story that I hope will inspire them. And as he always said, ‘Keep going no matter what,’” he echoed. “No matter how hard it is for Filipinos, and how hard it is sometimes to deal with race, especially in the US sometimes, it’s even more difficult for Blacks,” he added.

In an era still grappling with inequality and fear, Meily’s book becomes more than biography — it becomes a mirror. It reflects not only the lives of two men, but the systems they challenged, the costs they bore, and the light they refused to let go out.

A stage light, a lamp

Scenes from the memoir were also brought to life with performances by Jeremy Domingo, Nelsito Gomez, Maritina Romulo, and Tarek El Tayech, under the direction of Leo Rialp. The actors took on the roles of PR persons, Wall Street titans, and ghosts of memory — underscoring the theatrical scale of Lewis’ life and the emotional weight Meily carries in telling it.

During the Q&A, Meily also teased a stage adaptation, perhaps even a film. Still, Meily is less preoccupied with format than with message.

“I do want to thank Loida Lewis,” he said of Lewis’ widow. “Even though this book tells a very different story from her story of her husband, and from the very first version of her husband’s biography, which I held out, when I was his PR man,” he said. “I want to thank her for giving me the space to be honest.”

Honesty, for Meily, means reckoning with the full cost of ambition.

“I think ambition is important. I think success is important,” he addressed the younger audience members. “But I don’t think you should lose things along the way. Because at the end of your life, you’re not going to regret that you didn’t work harder. What you are going to regret when you’re on your deathbed is not spending more time with your loved ones.”

That hard-won wisdom is threaded throughout the memoir: the immigrant who believed in the American dream, the tycoon who demanded more than America was willing to give, and the shared sacrifices that both men — one Black, one brown — had to make. The personal becomes political when dreams collide with structures built to exclude. And yet, both Meily and Lewis insisted on breaking through.

Meily closed the afternoon with a line from the scripture: “Man does not light a lamp and hide it under a basket.” The light Lewis carried — fierce, flawed, unrelenting — still burns. Through this book, and through those who read it, it keeps shining.

“And I hope to keep that light burning for everyone to see,” Meily said, “and give light to everyone in this room, and outside this room.” – Rappler.com